Corporate

Governance

Inspection

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

April 2010

Contents

Executive summary 3

Recommendations 7

Detailed report 9

The Council 13

The Mayor and his Cabinet 20

Officers 24

Appendix 1 – Full list of members of Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council for

municipal year 2009/10 27

Appendix 2 – Detailed evidence supporting former Interim Chief Executive

section 31

Appendix 3 – Staff survey results 36

Appendix 4 – Corporate governance inspection key lines of enquiry 39

Appendix 5 – Details of work undertaken and interviews 41

Executive summary

Executive summary

1 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council (the Council) is failing.

2 The Council is not properly run and as a result it is failing in its legal obligation to make

arrangements to secure continuous improvement in the way in which it exercises its

functions, having regard to a combination of economy, efficiency and effectiveness.

Those leading the Council – the Mayor and Cabinet, some councillors and some

officers – do not collectively have the capacity or capability to make the necessary

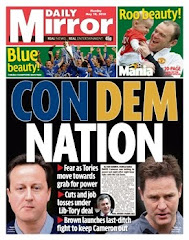

improvements in governance. The Council will not improve without significant and

sustained support from external bodies.

3 This corporate governance inspection was undertaken because of repeated evidence,

over more than 15 years that the Council is not well run. Until the recent ministerial

intervention in children's services, the Council had been successful in deflecting all

previous attempts to address its problems (despite those problems having been

accurately diagnosed in a Public Interest Report and a separate Ethical Governance

Healthcheck) whilst allowing poor and failing services to continue. A poor rating for

children's services for two years, a red flag in the Comprehensive Area Assessment for

poor prospects for children and young people, and the recent tragic events in Edlington

are the clearest examples of this. We conclude that the desire to pursue longstanding

political antagonisms is being given priority over much-needed improvements to

services for the public. The people of Doncaster are not well served by their council.

4 The Comprehensive Area Assessment concluded in December 2009, that the Council

performs poorly. It does not do enough to meet the needs of its most vulnerable

people, does not safeguard children, and has not been good at helping vulnerable

people find a home. Too many children underachieve at school, and too many are

excluded from school. Whilst some services are improving, for example adult services,

the neighbourhoods and communities services and the benefits services, many other

issues remain. Crime levels need to reduce further, people need to be helped to lead

healthier lives, more decent homes are needed, public spaces need to be cleaner, and

local people need better skills so they can get the new jobs that are becoming

available in the area. People’s satisfaction with the Council is low.

5 Good governance is about running things properly. It is the means by which a public

authority shows it is taking decisions for the good of the people of the area, in a fair,

equitable and open way. It also requires standards of behaviour that support good

decision making – collective and individual integrity, openness and honesty. It is the

foundation for the delivery of good quality services that meet all local people’s needs. It

is fundamental to showing public money is well spent. Without good governance

councils will struggle to improve services when they perform poorly.

6 There are three inter-related issues which mean that Doncaster Metropolitan Borough

Council is failing in its legal duty to make arrangements to secure continuous

improvement in the exercise of its functions. These three issues are individually

divisive and collectively fatal to good governance, each serving to compound and

magnify the negative impacts of the others. These issues also mean the Council lacks

the capacity or capability to improve in the next 12 months.

3 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

Executive summary

7 The three issues are as follows.

• The way the Council operates to frustrate what the Mayor and Cabinet seek to do.

• The lack of effective leadership shown by the Mayor and Cabinet.

• The lack of leadership displayed by some chief officers, and the way they have all

been unable to work effectively together to improve services.

8 The following paragraphs are a summary of the key issues arising within the body of

this report, which support our conclusion that the Council is failing in its duty under

section 3 of the Local Government Act 1999 (the duty to make arrangements for

continuous improvement) and is unlikely to improve without significant support from

outside.

9 The Council, and key councillors within it, are not working constructively with the

Mayor or with partners to achieve better outcomes for the people of Doncaster. Some

influential councillors place their antagonism towards the Mayor and Mayoral system,

and the achievements of their political objectives, above the needs of the people of

Doncaster, and their duty to lead the continuous improvement of services. The

Scrutiny process within the Council, which could act to hold the Mayor and Cabinet

properly to account, and help him develop his policies, is instead being used to

undermine the Mayor, and develop separate policies and budgets. The process of

budget-setting itself is not robust.

10 Decision making in key areas is too slow. The Local Development Framework, a key

document setting out development priorities and proposals, is still not agreed.

Decisions around Building Schools for the Future have been delayed, and external

capital funds put at risk, because of indecision. Discussions between the Council and

the arm’s length management organisation (ALMO) for housing – St Leger Homes –

about what work the Council wants done to certain categories of homes in the Decent

Homes programme have been going on for ten months. Discussions with the primary

care trust about funding for a new health centre to allow Council and NHS staff to work

together have been delayed by ongoing argument within the Council. The people of

Doncaster are at risk of losing out because of these failures. Other parts of South

Yorkshire have already made key decisions in these policy areas, and are already

delivering positive changes for their residents.

11 The way in which the former Interim Chief Executive was recruited in January 2010 is

a clear example of poor governance. The Council failed to live up to minimum

governance standards, and persevered with an appointment process they were

advised, by external legal experts, was flawed. The former Interim Chief Executive,

who was until his appointment the Council’s Director of Resources and Monitoring

Officer, failed to behave in a way that lives up to the required standards of behaviour.

He undermined perceptions of the role of Chief Executive as an impartial servant of the

Mayor and the Council.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 4

Executive summary

12 The Mayor does not always act in a way which demonstrates an understanding of the

need for an elected Mayor to lead his authority and represent all the people in

Doncaster. Some of the behaviours adopted by the Mayor and some Cabinet members

have failed to meet required standards, and serve to reinforce antagonisms from

certain groups within the Council. This contributes to the Mayor often failing to achieve

consensus around his key proposals.

13 More generally, officers have failed to act corporately, have struggled to provide

leadership, and have not acted as a team. Some have become used to the

dysfunctional politics of the Council, and no longer seek to maintain proper boundaries

between the respective roles of officers and councillors. Some officers have stopped

seeking political support for new strategic service plans, and seek to deliver them

without political discussion.

14 Good governance is fundamental to the proper running of public organisations. We

have considered whether the Council meets minimum standards of governance in six

areas: purpose and outcomes; functions and roles; values and behaviours; decision

making; capacity and capability; and engagement. We have also considered whether

we think the Council has the ability to improve, by itself, in these areas.

15 Our conclusions are set out in the table below. Our judgement is that the Council fails

to meet minimum standards in all six of the areas we considered, and lacks the

capacity to improve sufficiently in any of them without external support.

1 Purpose and outcomes of the Council

are confused, key decisions are being

delayed with a result that outcomes for

local people are not being delivered, and

value for money is not being delivered.

We do not think this will get better in

the next 12 months without external

help because of the track record of

problems, principally relating to

longstanding political antagonisms

within the Council.

2 Functions and roles are unclear,

responsibilities are not understood and not

respected, and the Council’s leaders do

not work effectively together. The

Overview and Scrutiny process is

operating as a separate source of

executive policy making.

We do not think this will get better in

the next 12 months because the

Council has shown itself unable to

work within clearly defined functions

and roles even when these have been

clearly set out.

3 Values and behaviours do not meet

minimum requirements. Some councillors

and a few staff are not working within the

ethical framework, are behaving in ways

which do not exemplify good governance,

and the Council is not learning adequately

from issues and complaints that arise.

We do not think this will get better in

the next 12 months because bad

behaviours are entrenched amongst

certain councillors and officers, some

of whom seem unable to distinguish

what is appropriate from what is not.

5 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

Executive summary

4 Decision making is not rigorous or

transparent. Key decisions relating to

schools, housing, and economic

development have been delayed due to

political antagonism within the authority.

Good quality information and advice is not

consistently used to make decisions and

risk management is inconsistent and does

not adequately cover partnership

objectives.

We do not think this will get better in

the next 12 months because the

process of decision making is a victim

of the antagonisms that exist within

the Council.

5 Capacity and capability within the

Council is insufficient to deal with the

problems it faces. Skills and knowledge

are available, but do not make a difference

to the way key individuals behave. The

Council has shown itself unable to respond

to previous attempts to help it because

behaviours are entrenched.

We do not think this will get better in

the next 12 months because the

response of the Council to previous

criticism has been to appear to comply

with recommendations made, whilst

actually continuing the same

destructive behaviours.

6 Engagement by the Council is

inadequate, both internally with staff, and

externally with partners and the people of

Doncaster. Key groups of people within

Doncaster find it hard to get their voices

heard.

We do not think this will get better in

the next 12 months because of the

entrenched attitudes of key decision

makers within the Council to the need

for, and benefits of, dialogue and

engagement with staff, partners, and

the public.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 6

Recommendations

Recommendations

16 The Council is failing in its legal obligation to make arrangements to secure continuous

improvement in the way in which it exercises its functions, having regard to a

combination of economy, efficiency and effectiveness.

17 We recommend that the Secretary of State should exercise his powers under

section 15 of the Local Government Act 1999 to give a Direction or Directions to

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council. Should the Secretary of State accept

our recommendation, the form and content of any Direction(s) will be a matter

for him to determine. However, it is our view that the purpose of the Direction(s)

should be to address the deep-seated culture of poor governance identified by

our inspection.

18 More specifically, the objectives of any Direction(s) should be to ensure that:

• the behaviour of the Mayor and some key councillors is no longer allowed to

obstruct the proper governance of the council;

• the role of the Mayor and Cabinet as the Executive is properly supported by

officers, and the Overview and Scrutiny function ceases to operate as if it

were an alternative Executive function;

• bullying and intimidating behaviour is eliminated;

• there is a rapid improvement in the performance of key services;

• the Council plays an effective role in working with external partners to

improve the prospects for the people of Doncaster;

• a high calibre Chief Executive who commands the respect of the Mayor and

the Council is in place; and

• under the leadership of a new Chief Executive, the chief officers work

collectively to deliver service improvement.

In the context of the above, it should be recognised that the Council has a long

history of responding to recommendations but failing to address the real cause

of its difficulties: the poor behaviour of key individuals. As such, the Secretary

of State may wish to consider the immediate suspension of some or all of the

functions currently undertaken by the Executive and Council, and the

appointment of commissioners to be responsible for the administration of

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council. However, if the Secretary of State

considers it appropriate for the Council to retain its functions and make the

necessary improvements, he may wish to consider the following actions.

7 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

Recommendations

Establishment of an Improvement Board

To oversee the effective implementation of the Direction(s) issued by the

Secretary of State an Improvement Board should be established, chaired by a

suitable individual appointed by the Secretary of State. The Board should

comprise senior figures with expertise in local governance from outside

Doncaster.

Failure by the Council to make adequate progress on the objectives set out

above, as determined by the Improvement Board, should lead to the Secretary of

State considering the suspension of some, or all, of the functions currently

undertaken by the Executive and Council.

The behaviour of the Mayor and councillors

The Secretary of State should put in place a package of measures to hold the

Mayor and councillors to account for their behaviour, and to build confidence

inside and outside the Council that poor behaviour will be tackled effectively.

This could include:

• reviewing the terms of reference and membership of the Standards

Committee (retaining an independent chair) to ensure that it is effective and

perceived as an effective safeguard by officers and councillors; and

• ensuring that a strong Monitoring Officer is in place and strengthening the

whistleblowing arrangements to encourage reporting of poor behaviour.

Delivering effective Executive and Scrutiny functions

The Improvement Board should ensure that the proper roles of the Council's

Executive and Overview and Scrutiny functions are established and adequately

and appropriately supported by officers.

The elected Mayor should be required to seek support from a suitable mentor,

chosen by him from a list of suitable individuals suggested by the Secretary of

State.

Effective officer leadership

The Improvement Board should oversee the process by which the Council

appoints a high calibre permanent Chief Executive who commands the

confidence of the Secretary of State, the Mayor and the Council.

The newly appointed Chief Executive should ensure the other chief officers work

collectively to improve the quality of governance, decision making and services

within the Council, within the context of an effective performance framework for

the Council and its staff.

The Improvement Board should ensure that the Chief Executive has access to

the level of support needed to deliver the substantial organisational change and

development necessary.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 8

Detailed report

Detailed report

Background to Doncaster

19 Doncaster sits within the area of South Yorkshire, close to the major conurbation of

Sheffield. It consists of a large, mainly rural area and three significant towns –

Doncaster, Mexborough, and Thorne. Many of the smaller towns and villages have a

history closely associated with coal mining. It has a population of some 291,000

people. 3.5 per cent of the population come from a black or minority ethnic

background; some 4,000 are gypsies and travellers; and over 2,000 are new economic

migrants.

20 The area has a number of natural advantages, including its location and its ready

accessibility by road, rail, air and water. The Council has been successful in promoting

the physical regeneration of the Doncaster town centre, with new buildings, shopping

centres and industrial units much in evidence.

21 In the last five years, the number of jobs in Doncaster has increased. Employment has

increased as has the number of local businesses, enabling residents to improve their

skills.

22 However, these improvements have not reduced rates of worklessness and have not

enabled Doncaster to improve relative to other places in the Yorkshire and Humber

region or in the country. Doncaster is still in the bottom 25 per cent, both regionally and

nationally, for many economic indicators.

23 Partners’ ambitions are for Doncaster to be a centre for economic growth in the

Yorkshire and Humber region. Recent research by Northern Way (a think tank set up

to support the development of the northern areas of England) suggests that faster

economic growth could be secured by closer working with the Sheffield City Region

and developing stronger economic links with Sheffield.

24 People in Doncaster are less well off, are more likely to be unemployed, and less likely

to be healthy than the average for similar types of authority; all of which means a

greater demand for public services and a greater need for an effective and well-run

local council.

25 Average numbers of 11-year old children reach the expected level in their tests. At age

16 achievement in exams is about the same as in similar authorities, although below

the national average. The number of young people aged 19 with the higher level

qualifications and skills required of many modern jobs is below similar authority and

national averages.

26 The level of new businesses registering for VAT is the sixth worst in Yorkshire and

Humberside, and in the lowest 25 per cent of authorities nationally. In 2009,

55 per cent of homes failed to meet the government’s decency standards, which again

placed Doncaster in the worst 25 per cent of authorities nationally.

9 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

Detailed report

Political context

27 The current Mayor was elected in June 2009, as a representative of the English

Democrat party. There are no other English Democrats on the Council. Another

independent was second in the mayoral vote, with the main political parties further

behind.

28 The Council's composition is shown in the table below. A full list of Councillors from

each group is set out in Appendix 1. One-third of Council seats will be up for election in

May 2010.

Number Party

26 Labour Nine chairs and six vice chairs, including:

Chair of Chief Officers Appointment Committee;

Chair of Chief Officers Investigatory

Sub-committee; Chair of Overview and Scrutiny

Management Committee; and Chair of Council.

12 Liberal Democrat Five chairs and three vice chairs, including:

Employee Relations sub-committees; JNC

Chief Officer Appeals; Economy and Enterprise

Overview; and Scrutiny Panel.

9 Alliance of Independent

Members Three chairs and four vice chairs, including:

Safer, Stronger and Sustainable; and Overview

and Scrutiny.

9 Conservatives One chair and four vice chairs, including:

Chair of Healthier Communities Overview and

Scrutiny; and Vice Chair of Awards; Grants and

Transport (Appeals); and Elections and

Democratic Structures Committee.

4 Community croup

3 Non-affiliated

independents

1 English Democrat Mayor

64 Total

29 The Cabinet consists of:

• the Mayor (English Democrat);

• three Conservative councillors; and

• three independent or unaffiliated councillors.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 10

Detailed report

The history of Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council's governance

30 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council has a troubled history of poor governance.

The negative perceptions created by the ‘Donnygate’ affair, which resulted in 21

councillors being convicted of fraud, hangs over the area and over the Council.

31 In the aftermath of the Donnygate affair, a mayoral referendum was instigated in 2001,

and the people of Doncaster voted to adopt the elected mayoral system of local

government. Martin Winter, standing as a Labour candidate, became the first elected

Mayor of Doncaster. Mayor Winter, who had been re-elected in 2005, became an

independent Mayor in 2008, following increasing difficulties between him and the

Labour group within the Council. He chose not to stand again in the mayoral elections

of 2009. Peter Davies, of the English Democrat Party, was elected as Mayor in June

2009.

32 Further problems with governance emerged in 2005. The then Chief Executive

(managing director) made allegations of improper conduct by the Mayor. The police

investigated these allegations, but no prosecution was brought. In August 2006,

allegations were made about the Chief Executive's behaviour, and after protracted

discussion the Chief Executive left the Council under a compromise agreement in

December 2006. A Public Interest Report from the District Auditor in May 2008

reflected on the issues raised by the disagreement, and on a wider set of underlying

governance issues within the Council. This contained ten recommendations, relating to

achieving good governance, implementing chief officer performance reviews, the

drafting of disciplinary reports, and about members' impartiality in disciplinary matters.

These were pursued through a Governance Improvement Plan overseen by an

independently chaired Governance Reference Group. In 2009, the District Auditor

concluded that the Council had finally implemented the ten recommendations from his

Public Interest Report. However, despite the recommended processes having been put

in place, it is clear that the behaviour of certain key individuals has not improved.

33 In 2008, the Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families judged children and

young people’s services in Doncaster to be so poor as to require ministerial

intervention. An independently chaired Improvement Board was set up in April 2009,

but has struggled to radically improve children’s services so far, in part because of the

ongoing political antagonisms within the Council and the failure of the Council to see

the issues as relating to all Council services, not just children’s services. At the same

time, Doncaster's Safeguarding Children's Board was exhibiting serious failings. The

tragic events of the Edlington case, which occurred before the appointment of the

independent Chairman, are only the latest in a series of failures by the Council to keep

children safe.

34 In February 2009, at the Council’s request, the Improvement and Development Agency

(IDeA) of the Local Government Association undertook an ethical governance

healthcheck, which was published June 2009. The healthcheck concluded the lack of

acceptance of the mayoral model by councillors appeared to be a key factor in the

difficulties the Council was having. The healthcheck highlighted behaviours that were

‘venomous, vicious, and vindictive’. Both the Public Interest Report and the

healthcheck have as a consistent theme the antipathy of certain councillors to the

elected mayoral model.

11 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

Detailed report

35 In January 2010, the then Chief Executive of the Council chose, at short notice, to

leave the Council. This triggered the series of events described at Appendix 1 which

led to the appointment of an Interim Chief Executive, in circumstances of considerable

acrimony. This, the history of poor governance within the Council, the record of poor

performance of some services, and the slow improvement of others; and the potential

loss of public confidence caused by the Edlington case, led the Audit Commission to

conclude a Corporate Governance Inspection was required.

The issues

36 There are three inter-related issues which prevent the Council from reaching minimum

standards of governance, and mean that it both fails in its duty to secure continuous

improvement and has neither the capacity nor capability to improve over the next

12 months. These three issues are individually divisive, and collectively fatal, to good

governance and to clear and speedy decision making. Each issue compounds and

magnifies the negative impact of the other failings and contributes to the Council failing

to meet its duty to secure continuous improvement. As a result, the people of

Doncaster are being let down by their Council.

37 The three issues are as follows.

• The way the Council operates to frustrate what the Mayor and Cabinet seeks to do.

An example of this is the way in which the former Interim Chief Executive was

appointed, and the resulting antagonism between him and the Mayor.

• The lack of effective leadership shown by the Mayor and Cabinet.

• The way some individual chief officers behave, and more generally the way officers

have struggled to work together collectively to improve services.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 12

The Council

The Council

The Council, and key Councillors within it, are not working constructively with the

Mayor or with partners to achieve better outcomes for the people of Doncaster. A

number of councillors put individual political aims and antagonisms above the needs of

the people of Doncaster.

38 In a well-governed mayoral authority the council should:

• accept the democratic mandate of the Mayor;

• be clear about the limits of its role in developing policy;

• work collectively with the Mayor and Cabinet to help them develop the most

coherent set of policies for the local people;

• enable officers to develop priorities into clear, costed plans of action which are

shared and agreed with partners;

• adopt leadership styles which are open, inclusive, and engender trust from staff,

other partners, and the public; and

• act as ambassadors for the Council in the wider area and with partners.

The democratic mandate

39 The attitude of some key councillors is fundamental to the failure of the Council to

improve over recent years, despite repeated involvement by external bodies. These

individuals are well known within the Council, and their names came up repeatedly

during the course of our inspection. They come principally, but not exclusively, from

the Labour group. They are long serving local politicians, and are highly skilled and

knowledgeable in the working and decision making processes of local government.

They occupy key positions of power, within the Council Chamber, within key

committees involved in appointing, and investigating disciplinary matters, for chief

officers; and within the Overview and Scrutiny process.

40 The Council was the subject of a Public Interest Report by the District Auditor in 2008.

It concluded the Council had failed to achieve proper standards of governance. The

actions of a few councillors, and of some officers, fell short of these standards. He

concluded the breakdown in relationships between the then Mayor and the then Chief

Executive (managing director) in part reflected existing tensions between the Mayor

‘and a key group of Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council Labour councillors’. The

District Auditor issued ten recommendations to improve governance within the Council.

41 In 2009, in part to support the Council’s work to respond to the District Auditor’s

recommendations, the Council commissioned IDeA to undertake a further check of

governance. This was called the ethical governance healthcheck. The healthcheck

highlighted councillor behaviours that were ‘venomous, vicious, and vindictive’.

13 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

The Council

42 The healthcheck again highlighted that ‘a majority of councillors expressed the view

they would prefer a different model of governance’. The healthcheck concluded the

lack of acceptance of the mayoral model appeared to be ‘a key factor in the breakdown

of trust and communication which is currently [in early 2009] facing the Council’. In

reporting this healthcheck back to Full Council in 2009, the peer Member on that team

said ‘several of you [Councillors] put your hatred of the Mayor above your love of the

people of Doncaster’.

43 In both the Public Interest Report and the IDeA healthcheck there is thus a consistent

theme of a set of councillors, many of whom continue to resent the end of the historic

committee system, who oppose the elected mayoral system. They would, even without

an elected mayor, find the reduced policy-making opportunities within the modern

Leader, Cabinet and Overview and Scrutiny model difficult to accept. Their actions

undermine the Council’s ability to function effectively.

44 The hostility towards the mayoral system transcends individual mayors. It became a

constant feature of the mayoralty of Martin Winter, who ceased to be a member of the

Labour Party in 2008, and has shown no sign of abating under Mayor Davies. Mayoral

candidates from the main political parties have failed in the third mayoral elections, and

discussions with the public as part of this inspection revealed considerable anger at

what were perceived as the disrespectful and condescending attitudes of some local

councillors.

Work to help the Mayor and Cabinet or Council role in developing policy

45 The dysfunctional relationship between the Council and the Executive (the Mayor and

Cabinet) is most clearly seen in the way in which the Overview and Scrutiny function,

and particularly the Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee (OSMC), has

been developed and allowed to work within the Council. Properly run, Overview and

Scrutiny should provide a key balance to the executive power of the Mayor by

scrutinising decisions and actions or making recommendations about the exercise of

executive functions. It does fulfil that function in Doncaster. During the last nine

months, OSMC and the four standing panels have made 162 recommendations to the

Executive, of which 79 have been accepted and 83 rejected. However, it also operates

as if it is a separate Executive function within the Council, developing its own policy

and budget, with the aim of marginalising and weakening the democratically elected

Mayor. We were given evidence that this is not a new phenomenon, and that this

separate function had been developing over a number of years.

46 It is perfectly legitimate for OSMC to play a role in developing the budget. The

Council's constitution states that OSMC ‘will, at its discretion: Assist the Full Council

and the Executive in the development of its budget and policy framework by in-depth

analysis of policy issues.’ The Council's constitution also makes it clear that although

OSMC is generally entitled to develop its own work programme in some areas, its role

in relation to the Budget and Policy framework is set out in the relevant part of the

Council's procedure rules. These rules require it to respond to proposals in the Mayor's

budget and do not envisage OSMC developing its own budget.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 14

The Council

47 However, the role played by OSMC in setting the 2010/11 budget went beyond the

provision of assistance or the exercise of scrutiny. It amounted to a separate process

leading to the preparation of an alternative budget to that of the Mayor. Officers were

required to service both the development of a Mayoral budget, and also support a

six-month long process of developing an OSMC budget in wholly inappropriate levels

of detail. There was no sense of OSMC seeking to scrutinise, add value to and make

recommendations about the Mayoral budget, but rather of a deliberate attempt to

create a separate budget. Detailed budget templates, broken down by service, were

discussed and refined with OSMC, and from November onwards were often discussed

with OSMC before being discussed with Cabinet.

48 Officers did attempt to make the budget process less politically divisive, for example by

exploring with the Mayor options for a smaller cut in council tax. The Mayor states that

he was prepared to compromise on his manifesto commitment of a 3 per cent

reduction, and proposed a 2.6 per cent reduction as an alternative. Officers found him

unwilling to explore whether this could be phased over a series of years, or delivered in

a later year of the mayoral term.

49 The opposition of Full Council to the mayoral proposal to reduce council tax by

3 per cent, and their advocacy of a 3 per cent increase to ‘protect services’ should be

seen in the context of that same Council having agreed in each of the four preceding

years a council tax rise pegged to the Retail Prices Index (in other words, a real terms

increase of nil).

50 The Mayor’s budget was voted on and rejected by Council on 22 February 2010, and

the alternative budget of OSMC was voted on and approved by Council on

22 February 2010.

51 To understand the implications of this it is important to remember that the elected

Mayor is the principal executive authority within the Council. The purpose of Overview

and Scrutiny is to hold him and his Cabinet to account for the way they exercise this

authority, and to contribute to evidence-based policy making. But Doncaster’s OSMC

is being used not to scrutinise the Executive, but to bypass it. It is a mechanism for

hindering the elected Mayor’s capacity to act and leaving him largely powerless. This

results in deadlock and undermines the Council’s ability to fulfil its duty to make

effective arrangements for the continuous improvement of its functions.

The role of officers

52 Officers acquiesce in this inappropriate use of OSMC. Their motivations for doing so

are mixed, but in general are suggestive of officers who have come to accept it as a

legitimate manifestation of a member-led authority and who lack the collective ability to

withstand unreasonable demands from senior councillors.

53 Even some councillors who have attempted to stay impartial report that they find it

difficult now to trust officers. They fear that some officer advice has become unduly

influenced by the power wielded by one political faction or the other. This loss of trust

in the impartiality of officers is inevitably corrosive. For example, recent positive news

about improvements in Adult Services has not been fully believed.

15 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

The Council

54 It is also important to note that the budget proposals developed through this process

are not addressing the strategic issues facing the Council. There is a disproportionate

focus on minutiae (such as saving £1,700 on laundering tea-towels) while leaving

major savings, in one case amounting to over £500,000, still to be identified.

55 Even at the detailed level, the budgetary process is inadequate. Savings proposals in

children's services have not been discussed with partners, and staff are unclear what

the proposals mean for their posts. There is no reference in the Children's Services

Directorate budget to the planned reduction, by one-third, in the use of external

out-of-borough placements for children and young people. Education budget proposals

are not accompanied by a costed workforce strategy to explain the cost implications of

eventualities such as qualified social workers opting to fill current vacancies.

Leadership styles of councillors

56 The behaviour of a small but highly influential group of councillors plays an important

role in creating the climate in which officers, and other councillors, operate. It is a

major factor in preventing the Council from effectively improving its functions.

57 We have been provided with consistent evidence of behaviours from some key

councillors that clearly amount to bullying and harassment. These include comments

such as ‘we have long memories’ and ‘we will get you’ made to officers when in the

course of their professional duty they have given advice which certain councillors are

uncomfortable with or dislike. In this environment, certain officers have left the Council,

certain officers remain but are weakened, and certain officers persevere with trying to

deliver better services in spite of the political environment in which they operate.

Complaints are not always taken to Standards Committee because it is perceived as

weak and ineffective in the political environment that exists.

58 As part of this inspection, we undertook a staff survey. We had over 1,400 responses

in the two weeks in which staff had the opportunity to respond. Asked whether they

agree or disagree with the statement ‘There is clear and effective leadership within the

Council by Councillors, 60 per cent of staff responding disagreed or strongly

disagreed. An additional 21 per cent didn’t know.

59 Our staff survey showed a difference of view amongst staff as to whether the Council’s

culture promoted respect. Asked whether they agree or disagree with the statement

‘The Council’s culture promotes mutual respect between councillors and staff’

34 per cent agreed or strongly agreed. However, 57 per cent disagreed or strongly

disagreed. A further 13 per cent didn’t know.

60 There is no planned and effective approach to borough-wide consultation with

residents. Residents feel they are informed rather than consulted. The Council used to

have a Citizens Panel, but this has been disbanded. The Council will be unable to

improve services for all Doncaster residents unless it listens to all of its residents about

their needs. The Council's Community Involvement Strategy 2010-2013 identifies that

current practice is poor on a number of counts, including that insufficient information is

available to the public, and relies on too few methods of involvement, missing out

several groups' voices.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 16

The Council

61 The recent Place Survey revealed that 22 per cent of Doncaster people think they can

influence the decisions made by the Council. This puts the Council in the worst of

14 comparable councils. The average for the comparator group is 26 per cent.

Being ambassadors and working with partners

62 The Local Development Framework also provides an example of the way in which the

antagonistic political environment within the Council results in slow decision making,

and puts at risk better outcomes for local residents.

63 The Local Development Framework is a key document setting out spatial and strategic

development priorities and proposals, which have a fundamental impact on partners

both within Doncaster and on other councils in the South Yorkshire area. The plans

have been significantly delayed, and while they have now been revised and updated

will now have to go back to Overview and Scrutiny. Officers foresee a difficult time

politically as historic antagonisms are played out again between the competing political

factions. Uncertainty remains about whether it will be possible to broker a political

consensus around this key policy.

64 The slowness of decision-making is also impacting on the prospects for children and

young people within Doncaster. The Building Schools for the Future programme offers

opportunities for significant capital funding, but these are in danger of being

squandered because of the lack of clarity about critical budget decisions. Delays in

decision making have affected the NHS Local Improvement Finance Trust programme

and delayed agreement on a new health centre which would give opportunities for

Council social workers and health to work together. It is, of course, perfectly proper

that there should be political debate about this and other policies. But failure to make

decisions hinders officers from developing budgets. Still more important, it risks

depriving the people of Doncaster of investments that could be made in improving the

services they receive.

The appointment of the former Interim Chief Executive

65 The process of appointing the former Interim Chief Executive, Tim Leader, is

symptomatic of the fundamental governance failures which afflict the Council. It is a

prime example of poor governance processes at work. It also exemplifies the inability

of a key officer and some councillors involved in the process to see above their own

self interest and act for the greater good of the people of Doncaster.

66 The former Interim Chief Executive, who was previously the Monitoring Officer of the

Council, failed to behave in a way that lives up to the required standards of behaviour.

He undermined perceptions of the role of Chief Executive as an impartial servant of the

Mayor and the Council. The Council failed to live up to minimum governance

standards, and persevered with an appointment process they were advised by external

legal experts was flawed.

67 The process shows:

• a Monitoring Officer advising on matters in which he had a clear self interest;

• the Council rejecting internal and external advice, including legal advice;

17 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

The Council

• the Council persevering with a flawed process despite that advice; and

• the Council being willing to appoint, and then reaffirm, an Interim Chief Executive

with whom the Mayor had stated he could not work.

68 The way in which statutory chief officers of local authorities conduct themselves is

fundamental to good governance in any Council. The Head of Paid Service (also

known as the Chief Executive) is required to be the senior leader of the council’s staff,

have oversight of all council services, and act as an ambassador for the authority

externally. Crucially, they must be impartial, and be seen to be impartial.

69 Councils are also required to appoint a Monitoring Officer. That person cannot also be

the Head of Paid Service. The Monitoring Officer’s role is also crucial to good

governance, and theirs is the onerous task of having to advise councillors, and other

chief officers, if their proposed actions or behaviours stray to the point of illegality.

Again, their independence, impartiality, and good judgement are crucial.

Events leading to the appointment of the former Interim Chief Executive

70 The events around the appointment of the former Interim Chief Executive are

complicated. What follows is a summary of the considerable volume of evidence we

have received. A full chronology and explanation is given at Appendix 2.

71 Mr Leader came to Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council in September 2009, as

Director of Resources and as Monitoring Officer, through an external recruitment

exercise overseen by a recruitment agency. At his best he was seen as inspirational by

some Councillors and some staff. He was described by some as intelligent, giving of

clear direction and purpose, insightful and incisive. However, there were also contrary

views about Mr Leader. Some questioned his temperament, the level of his skills to

undertake what is a hugely difficult job, and also the extent to which his actions

through January and February 2010 were self-serving. He did not have the full

confidence of all of his chief officer colleagues.

72 The chronology of events at Appendix 2 show Mr Leader played an active part in

leading the advice to the Council, and to the Chief Officers Appointments Committee

(COAC), about the appointment process. We have seen no evidence that Mr Leader

expressed concern about the fundamental conflict between his ability to advise the

Mayor, Cabinet and Council impartially, and his being one of the likely beneficiaries of

the process about which he was advising.

73 The evidence we have received makes it clear that Mr Leader continued to advise the

Council on the process it should follow to appoint an Interim Chief Executive even after

it became clear that he was a leading candidate for that position.

74 Legal advice from Eversheds to the Cabinet on 19 January 2010 suggested

Mr Leader’s actions may have been contrary to the Employees Code of Conduct. In

Evershed’s view Mr Leader should have withdrawn from the process and declared an

interest.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 18

The Council

75 Further legal advice from Wragge & Co to Ms Leigh (Director of People, Performance

and Improvement) and Mr Roger Harvey (Interim Monitoring Officer), dated 1 February

2010, was clear. ‘The procedural objections can not be lightly discarded. They appear

to be serious, honestly held and substantial in terms of the importance of the

appointment’. They were also of the view that ‘Members must consider with great care

how the Council’s interest can lie in appointing to the post of Chief Executive, a

candidate with whom the directly elected Mayor says he cannot work with’[sic].

76 The legal advice also suggested two further defects with the procedure adopted by the

Council on 18 January 2010. The Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

Constitution was defective in not including within the COAC a voting member of the

Executive (in other words. the Mayor or a Cabinet member). Secondly, the resolution

of the Council on 18 January was not effective because statutory consultation and

objection to any proposed appointment had not taken place. Both procedural

requirements are contained in the Local Authorities (Standing Orders) (England)

Regulations 2001.

77 The Extraordinary Meeting of Council on 3 February 2010 was called to discuss again

the appointment of the Interim Chief Executive. The Interim Monitoring Officer,

Mr Harvey, and the partner from Wragge & Co both spoke to the meeting. Both

advised Council to refer the process back to COAC and get them to rehearse and

decide on the procedural and substantive objections to the process adopted on

18 January. It is unclear, had this happened, whether COAC would have been

reconstituted to include a member of the Executive, but in any event it was immaterial.

Full Council declined to send these issues back to COAC. They sat for six and a half

hours and re-affirmed Mr Leader’s appointment.

78 We have been told that in the period prior to the meeting on 3 February, key national

political figures from local government were in Doncaster speaking to their local

groups, and it has been suggested that they advised the groups to think very carefully

about respecting the wishes of the Mayor. If so, this advice was ignored.

79 We have highlighted the inappropriateness of Mr Leader advising on the process that

led to his own appointment. But this is not the only issue of governance that arises

from this episode. When engaged in appointing an interim Chief Executive, Councillors

were prepared to disregard independent legal advice that the process they were

adopting was flawed.

80 As a postscript to these events, there was subsequently a whistleblowing complaint

about the appointment process for the former Interim Chief Executive.

81 It should also be noted the District Auditor is currently seeking legal advice and is

awaiting the conclusion of this inspection before he decides whether there is any

action he needs to take in response to the Corporate Governance Inspection findings

in relation to the defects in the appointment process.

19 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

The Mayor and his Cabinet

The Mayor and his Cabinet

The Mayor fails to act in a way which demonstrates an understanding of how an

elected Mayor might lead his authority in an inclusive way with a view to building

consensus. Some of the behaviours adopted by the Mayor, and some Cabinet

members, fail to meet required standards.

82 In a well-governed mayoral authority we would expect the Mayor and Cabinet to:

• adopt leadership styles and behaviours which are open, inclusive, and engender

trust from staff, other council partners, and the public;

• discuss priorities with the rest of the Council and be seen to respond to the

Council’s feedback;

• work collectively with officers to develop those priorities into clear, costed, plans of

action, which are shared and agreed with partners;

• be clear and decisive about their political priorities; and

• act as ambassadors for the Council in the wider area, to work effectively with

partners.

Leadership styles and behaviours

83 The Mayor is not the cause of the Council's problems, which date back to a time before

either he or his predecessor were elected. However, the way he has set about his task

has tended to make those problems worse. He acknowledges that he is inexperienced

and the leadership he and his Cabinet provide has so far lacked the sophistication and

skill that would help the Council and its partners to deliver better services for the

people of Doncaster.

84 The Mayor was elected in June 2009. By his own admission this was something of a

surprise to him. He lacked any background in local government politics, but found

himself overnight in a position of considerable power and influence over the people of

Doncaster and the services they receive. His expressed views are unsympathetic to

many of the normal processes by which decisions are traditionally taken and policies

developed in local government.

85 The Mayor's views on issues of diversity and political correctness are well known, and

formed part of the platform on which he was elected. He is, of course, entitled to

pursue his political agenda as a democratically elected Mayor, and is doing so.

86 However as Mayor he has also certain responsibilities including, for example, a

statutory duty in discharging the functions of the Council to have regard to the need to

promote good race relations. Perhaps partly through inexperience, he seems

insufficiently aware that the way he expresses his views might compromise his ability

to discharge those responsibilities.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 20

The Mayor and his Cabinet

87 The Mayor’s statements about removing translation services, or there being 'no such

thing as child poverty' have led to confusion. Partners are unclear what they mean for

them, and for jointly-agreed objectives within the Borough Strategy and Local Area

Agreement, such as helping and supporting vulnerable groups. They have also caused

major concerns amongst vulnerable groups within Doncaster. Some staff, residents

including some from the black and minority ethnic communities, and representatives of

the voluntary and community sector, expressed concern that certain people within

Doncaster may see some of the Mayor’s comments as legitimising their racist and

homophobic behaviour.

88 In discussion, the Mayor is more balanced, and suggests that he accepts the need to

adhere to legal duties around racial equality and the need to address inequality and

poverty. He appears to accept the need for translation services to aid in the

safeguarding of vulnerable adults from minority backgrounds. However, his public

utterances, which he may see as serving a useful political purpose, have served

internally to confuse and de-motivate staff; externally to confuse partners; and publicly

to worry sections of the community who are already vulnerable.

89 Asked whether they agree or disagree with the statement ‘There is clear and effective

leadership within the Council by the Mayor,’ 67 per cent of staff responding to our

survey disagreed or strongly disagreed. An additional 16 per cent didn’t know.

Working with the Council

90 The Mayor and Cabinet find it difficult to work constructively with the Council. This is in

no small part due to the behaviours of some councillors. However, the Mayor is also

not averse to provocative and inflammatory statements and these serve to create

division when compromise and conciliation are required.

91 An elected Mayor requires the approval of the full Council for key decisions, such as

the budget. The Mayor, coming from a minority party (the English Democrats), has little

natural support within the Council and consistently struggles to capture enough votes

to secure his policies. His current Cabinet consists of three Conservative and three

independent members. Attempts to attract independent members to sit on the Cabinet

have caused acrimony and given rise to complaints.

92 It is in the context of this unstable and limited powerbase, that the Mayor’s attitudes

towards political leadership within the Council, and how to build consensus amongst

competing politicians and groups, becomes problematic. The Mayor has genuinely

tried to discuss matters of mutual interest, and has sought to make alliances with

groups and individuals in return for support. He has himself identified that at least nine

of his ten priorities could easily link to priorities already expressed within the Borough

Strategy.

93 However, the Mayor lacks the political skills to build and maintain consensus. His

offers for others to ‘get in touch’ are often not followed through, and he fails to

understand that simply saying ‘my door is always open’ will not result in dialogue

unless his behaviours, attitudes, and opinions also support a more collusive and open

approach. The Mayor has not responded positively to offers of help, for example from

IDeA. The Mayor has also decided to take the Council out of the Local Government

Association and the Local Government Information Unit from 2011.

21 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

The Mayor and his Cabinet

94 The Mayor, and the Council, are too insular in their approach, failing sometimes to see

the key links between Doncaster and the rest of South Yorkshire and the City Region.

This in turn may mean opportunities to improve with the rest of South Yorkshire are

missed. In addition, their lack of appreciation of issues relating to diversity risks

perpetuating inequality amongst the people who live within Doncaster. For example,

Council strategies do not feature children who come from gypsy and traveller families,

despite there being over 4,000 gypsies and travellers in the Doncaster area.

Working with officers

95 The Mayor is isolated, and has too often been unwilling to take advice. In his early

days he relied heavily on Mr Hart, the then Chief Executive. This had two

consequences. It took so much of the Chief Executive’s time that it affected his ability

to function as a strategic leader of the staff within the Council. It also created a

perception amongst some (already antagonistic) councillors that the Chief Executive

was becoming too friendly with the Mayor.

96 The induction process for the Mayor did not lead him to understand how the Council

works. In his view, considerable time was spent on key policy issues and service

concerns, but only belatedly was he told about the mechanics of how a mayoral

authority works: what key decisions are; the necessity to get key decisions through Full

Council; and the respective roles and powers of the Mayor, the Cabinet as Executive,

the Council, and the Overview and Scrutiny function. Others suggest that these

briefings did take place. Whatever the process, the result was that the Mayor only

belatedly gained an understanding of the processes that had to be adopted in relation

to certain decisions, and this resulted in further delay. It also increased the Mayor’s

frustration that as democratically elected Mayor it was proving so difficult to ‘get things

done’.

97 Recent events, and the divide between the Mayor and Cabinet and the Interim Chief

Executive only served to increase this isolation and underscore the Mayor’s frustration.

By the Mayor’s own admission, getting decisions taken was like ‘wading through

treacle’. This is further evidence in support of our conclusion that the Council has failed

to make proper arrangements to fulfil its duty of continuous improvement.

Clear and decisive

98 The Mayor’s, and some Cabinet members', bluff approach to dialogue also extends to

the way in which they relate to officers. Some officers report considerable pressure

being put on them to amend or alter professional advice. If advice is contrary to

expectations, then officers sense they fall out of favour. Clearly, this is not conducive to

a well-governed organisation or to a situation in which officers feel able to give

impartial advice.

99 In part, as a result of the political impasse within the Council, key decisions have been

slow to be taken or still remain undecided. Examples include decisions about the

Local Development Framework, which is described in Paragraph 63.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 22

The Mayor and his Cabinet

100 A further example of slow decision making, involving partners, relates to the decent

homes programme delivered with St Leger Homes – the ALMO. On becoming

Chief Executive in May 2009, the Chief Executive of the ALMO defined a series of key

decisions on which she needed clarity from the Council to enable her to deliver ALMO

and Council priorities. Examples included clarity on whether tower blocks were to be

included in Decent Homes Standard refurbishment plans, and if so to what extent –

just windows and doors, or full refurbishment to include repairing concrete and

improving thermal efficiency. The Chief Executive stated she needed these key

decisions by November 2009, thus giving six months for discussions and resolution. In

February 2010, three months after the deadline, and ten months after identifying the

issues that needed to be decided, there was still a lack of clarity, having discussed and

redrafted proposals around these programmes three times. We understand this

decision may now have been taken.

Working with partners

101 A further impact of the conflict within the Council is the confusion it creates with

partners about what the Council’s long-term priorities are. There are mayoral priorities

and there is a Borough Strategy, and partners and staff express confusion about how

these are linked. The corporate strategy also fails to link properly with individual

service development plans. The recently defined strategic vision for children and

young people is not yet set firmly within a clear corporate strategy as this corporate

strategy still consists of the priorities inherited from the previous Mayor.

102 The Cabinet has limited experience. Whilst some portfolio holders are acc

others are inexperienced and appear less comfortable with the strategic leadership

required. Some have clear views of their own, and in certain cases these have cause

confusion and concern with partners. The ALMO, St Leger Homes, is in ongoing

discussion with the Cabinet, and portfolio holder, over the length of its managem

agreement. There are differing views about how long the ALMO agreement sho

for, but one consequence of the portfolio holder seeking a shorter term is that ALM

staff have become concerned about their job security. Tenants have also become

concerned that their homes, scheduled to be improved in the latter stages of the

Decent Homes process, may not get the necessary funding as they believe the ALMO

may not exist in the longer term. This is both unhelpful and destabilising.

The rejection o

omplished,

d

ent

uld last

O

103 f the usual methods of working with others is also slowing the progress

c

n.

partners can make. For example, the Mayor’s chairmanship of the Local Strategi

Partnership Board – Discover the Sprit (the DTS Board) - is causing some confusio

23 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

Officers

Officers

The former Interim Chief Executive failed to act properly. More generally, chief officers

have not always acted corporately, have struggled to provide leadership, and have not

acted as a team. Some have become used to the dysfunctional politics of the Council,

and no longer seek to maintain proper boundaries between definitions of the

respective roles of officers and councillors. Some officers have stopped seeking

political support for new strategic service plans, and seek to deliver them without

political discussion.

104 Despite the political environment in which they operate, and despite previous con

restructuring, some officers are highly credible and have succeeded in improving

services. Examples include the Adult Services Director, where a clear, logical and

methodical approach to service improvement, involving staff and partners, has secured

a rating from Care Quality Commission for 2009 of ‘performing well’, having previo

been rated as adequate and having been identified as a Department of Health priority

for improvement. The new Director of Children’s Services has considerable pers

credibility, and a clear sense of how much, and how far, the children's service still ha

to improve. Many officers and staff work tirelessly to deliver services of which they can

be proud. Too often, however, their successes are achieved despite, rather than

because of, the leadership they receive.

fused

poor

usly

onal

s

105 Some of the Council's services attract negative attention. The children's service is the

most notable and serious example, but others exist such as housing services, in

particular the level of voids, and housing services for vulnerable people. Corporate

leadership has failed to quickly and effectively deal with these serious weaknesses. A

reorganisation of the Council in 2005 is widely seen by staff at varying grades as

having been disastrous. It created a matrix management approach which left staff

confused, with several lines of accountability, and no clear recourse to advice when

problems arose. It has taken years to remedy the impact of this reorganisation, and

there remain some vestiges of it which chief officers know they need to correct (for

example the location of warden services in Neighbourhoods and Communities as

opposed to Adult Services).

106 The Council has had a consistently high rate of turnover of chief officers, especially

within children's services. This creates confusion, inevitably leads to new ways of

working and new strategic approaches from each chief officer, and prevents the

forming of a stable and effective corporate team. It also disrupts the ability of the

corporate management team to effectively discuss and respond to issues which cover

more than one departmental boundary. One example is the 2005 Every Child Matters

agenda, on which the Council has been consistently slow to respond. There has been

a failure to see that the issues in Every Child Matters relate not just to services for

children and young people but are connected with housing, regeneration, skills, health,

and the safeguarding of children in transition to adulthood. The Every Child Matters

agenda is therefore also relevant to partners in police, the NHS, and the voluntary

sector. The Council has been similarly slow in responding to the current policy on

children’s trusts.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 24

Officers

107 Allied to this high officer turnover is a high use of interim appointments to provide stop

gap cover. Whilst highly skilled in their own fields, such interims inevitably come with

their own ideas of how to ‘fix’ things, and in some cases have exhibited an

unwillingness to learn from chief officer colleagues, some of whom (for example in

Adult Services) already had a proven and effective track record of service

improvement in a Doncaster context. This failure to learn from colleagues internally

slows the speed of service improvement and again acts against a truly corporate and

shared approach being developed to services.

-

ired.

108 At the point the Secretary of State intervened in children's services, the Council

acknowledged its lack of capacity to manage children’s services, but the series of

interim directors, and continued use of interim and temporary staff in key functions

such as contact, referral and assessment has hindered safeguarding of children. There

are some signs of progress, such as a multi-agency resource panel, that has improved

access to placement for vulnerable children; and the continuation of high quality

provision by the Youth Service. The appointment of a permanent Director of Children's

Services from outside the Council and of two assistant directors, signals an opportunity

for stability and coherence that has been lacking for years.

109 However, a more corporate approach to improving children’s services is still requ

At a recent Corporate Leadership Team (CLT) meeting chief officers, led by the former

Interim Chief Executive, failed to properly discuss a corporate response from all

services to the need to serve children and young people better. A conclusion that the

improvement plan be brought back to CLT in ‘two or three months’ showed a worrying

inability to seize and drive corporately the most important issue the Council faces.

There was no sense of CLT taking corporate responsibility and providing tangible

support; rather it was just left to the Director concerned who had only recently arrived

at the Council.

110 Examples exist of good service provision, among them adults’ services,

Neighbourhoods and Communities and physical regeneration. There have also been

successes in job creation and new business starts. But there is a worrying attitude

amongst councillors and some staff that ‘services in Doncaster are good’. They are

not. There are clear failings in children's services, and whilst prospects for the future

look more promising than they have for a while, the current state of the service is weak

and not fit for purpose. Housing services received a red flag in the Comprehensive

Area Assessment in 2009, as a result of a high level of void (empty) properties and

poor provision for vulnerable groups. There are high levels of health inequality, high

levels of unemployment amongst local people, a relatively lowly skilled local workforce,

and a high level of non-decent homes.

111 Certain officers have suggested that, in part, frustrated at the slowness of decision

making and the acrimony involved when any political direction or agreement is

required, they have begun to seek to avoid political input into policy development and

delivery. This is, from one perspective, understandable, and may allow the Chief

Officer to ‘get on’. However, it runs the risk of undermining trust in officers amongst

councillors who remain impartial in the ongoing antagonism between Council and

Mayor. It also militates against a truly integrated and corporate approach to service

development and delivery, and therefore reduces the likelihood of sustained

improvement in services to the people of Doncaster.

25 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

Officers

112 Certain other officers have become accepting of the political dysfunction around them

Their acquiescence means that certain councillors remain able to act inappro

exercising Executive functions in policy development where they should not. This

acquiescence on the part of officers may be connected to instances reported to the

inspection team of bullying by councillors, and in one instance by another chief of

colleague. A number of chief officers did not trust the former

.

priately,

ficer

e.

113 we undertook a staff survey. Asked whether they agree or

Other governance failings

Interim Chief Executiv

As part of this inspection

disagree with the statement ‘There is clear and effective leadership within the Council

by senior officers,’ 47 per cent of staff responding agreed or strongly agreed. However,

42 per cent of staff disagreed or disagreed strongly. An additional 10 per cent didn’t

know.

114 The ongoing failures within children's services were one of the triggers that led to the

115 istently

il to be

116 ment is also critical of the Council’s delivery of value for money; the

king,

117 officers and was not

Corporate Governance Inspection. In children’s services communication is poor,

management is inconsistent and the Council does little to gather and act on the views

of staff. Communication is often via email, and staff report incidences of bullying using

email. Inconsistent management of children and young people’s teams leaves some

staff without information, support, or professional development. Despite this, staff

remain loyal to the Council but desperate for improvements to happen.

The Council's performance management is poorly developed and incons

applied. The Council’s self-assessment, which must be treated with caution as it was

prepared without input from Mayor, Cabinet or councillors, is nonetheless clear and

direct about the failings in performance management. It states that ‘the lack of

consistency in service delivery across the board and the tendency of the Counc

taken by surprise by poor performance stems from the lack of performance

management’.

The self-assess

lack of clarity of roles and behaviours; the firmly held and entrenched opposition to the

mayoral system; and the failure to live out defined values and behaviours. It also

recognises the need to improve the use of good quality information in decision ma

and the need to improve governance procedures with partners.

It is telling that this self-assessment was produced by certain key

a collective submission by the Mayor, Cabinet, councillors, and officers. Whilst honest

about certain aspects of governance as exist currently, the self-assessment is too

optimistic about the prospects of change for the future, and in particular seems to

underplay the difficulty of brokering any future political consensus where little has

existed before.

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 26

Appendix 1 – Full list of members of Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council for

municipal year 2009/10

Appendix 1 – Full list of members

of Doncaster Metropolitan

Borough Council for municipal

year 2009/10

Source: www.doncaster.gov.uk/about/chamber/default.asp?Nav=PartyList

Party or group Members

Community Group Party 4

Conservative Party 9

English Democrats 1

Independent or not affiliated to a party 3

Labour Party 26

Liberal Democrat Party 12

The Alliance of Independent Members

Group 9

Community Group Party

Member Political party or group role

Martin Williams Leader

Carol Williams Deputy Leader

Stuart Exelby

Nigel Hodges

27 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

Appendix 1 – Full list of members of Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council for

municipal year 2009/10

Conservative Party

Member Political party or group role

Barbara Hoyle Leader

Yvonne Woodcock Deputy Leader

Patricia Bartlett

Bob Ford

Allan Jones

Cynthia Ransome

Patricia Schofield

Jonathan Wood

Doreen Woodhouse

English Democrats

Member Political party or group role

Peter Davies

Independent or not affiliated to a party

Member Political party or group role

Andrea Milner

Mark Thompson

Richard Walker

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 28

Appendix 1 – Full list of members of Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council for

municipal year 2009/10

Labour Party

Member Political party or group role

Joe Blackham Leader

John McHale Deputy Leader

Susan Bolton

Elsie Butler

Richard Cooper-Holmes

Marilyn Green

Stuart Hardy

Beryl Harrison

Sandra Holland

Moira Hood

Eva Hughes

Mick Jameson

Barry Johnson J.P.

Glyn Jones

Ros Jones

Ken Keegan

Ted Kitchen

Ken Knight

Chris Mills

Bill Mordue

John Mounsey

Beryl Roberts

Craig Sahman

Tony Sockett

Norah Troops

Austen White

29 Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council

Appendix 1 – Full list of members of Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council for

municipal year 2009/10

Liberal Democrat Party

Member Political party or group role

Paul Coddington Leader

Eric Tatton-Kelly Deputy Leader

Kevin Abell

Jill Arkley-Jevons

Paul Bissett

Stephen Coddington

Clifford Hampson

Karen Hampson

Susan Phillips

Pat Porritt

Edwin Simpson

Patrick Wilson

The Alliance of Independent Members Group

Member Political party or group role

Garth Oxby Leader

Deborah Hutchinson Deputy Leader

Tony Brown

Peter Farrell

David Hughes J.P.

Mick Maye

Georgina Mullis

Ray Mullis

Margaret Pinkney

Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 30

Appendix 2 – Detailed evidence supporting former Interim Chief Executive section

Appendix 2 – Detailed evidence

supporting former Interim Chief

Executive section

Events leading to the appointment of the former Interim Chief Executive (Mr Leader)

1 Mr Leader came to Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council in September 2009, as

Director of Resources and as Monitoring Officer, through an external recruitment

exercise overseen by a recruitment agency.

2 Prior to Mr Leader’s appointment, in April 2009, Mr Hooper joined the Council as