Maverick British MP Galloway courts Muslim vote

Head of the Respect Party campaigns in London’s east end

Published On Sun May 02 2010

By Thomas Walkom

National Affairs Columnist

LONDON—George Galloway, the British MP deemed too dangerous for Canada, takes a final puff on his stogie, clambers to his feet atop the swaying, double-decker campaign bus, picks up his microphone and starts into what longtime advisor Ron McKay calls “the harangue.”

“Choose Respect on the sixth of May,” the 55-year-old Galloway booms out in his rich Scots brogue, as the song made famous by Aretha Franklin blasts from the speakers behind him.

“Stop the wars. Bring the armies home. Spend the money here. . . ”

Men with brown skin and women in headscarves smile and wave as the bus rolls though the Limehouse district of London’s east end.

Most white people don’t.

The only elected MP for Respect, a tiny left-wing party that pitches directly to Britain’s Muslim minority, Galloway is taking a big gamble in Thursday’s election. He’s given up his own seat to run in a new riding next door.

He acknowledges that the contest won’t be easy. The stereotypical Cockney east end has largely disappeared. In its place are low-income housing estates of Bangladeshi and Somali immigrants, interspersed with large pockets of what’s known here as the white working class.

Along the Thames, all of this is fringed by expensive riverfront condominiums.

Galloway knows he has no chance with the condo owners. He is gambling that he can get virtually all of the Muslim voters (they make up 40 per cent of the riding) plus the support of one or two thousand whites — particularly middle-class liberals.

But he has given up on the bulk of the white working class. And the favour is being returned.

“He’s is a bit of a prick really,” 19-year-old plumber Phil Thompson tells me as the candidate talks to voters in a shabby outdoor market. “I’m not too keen on him.”

Thompson, like many in this part of London, is a fervent supporter of the hard-right, anti-immigrant British National Party. “They stick up for their own,” he explains.

Indeed, throughout a day spent with the Galloway campaign, the sense of race is never far away.

Almost every brown person I interview likes Galloway. Stall merchant Rahan Rahman’s comment is typical: “I’ll vote for him; he speaks well and is telling the truth.”

Yet almost every white person is, at best, indifferent. “I don’t see the point of voting for a one-man party,” says antique dealer Tony Landau, a Labour supporter whose comments are also typical.

When the bus rolls into Millwall, a stronghold of the British National Party, Galloway’s team gets visibly nervous.

“Put on your helmets,” quips McKay. Nader Daher, a big man who acts as Galloway’s bodyguard, isn’t laughing. He moves in closer to the candidate.

But then election violence is not unknown here. Galloway is unpopular with Islamist fundamentalists because he’s trying to persuade Muslims to vote. And he’s unpopular with the BNP crowd for the same reason. He was physically attacked in a punch-up three weeks ago.

On this day, however, there are no serious incidents. One young white man walking a large dog yells at Galloway to “get off the f…ing estate.” An aide calls police, but in the end, nothing happens.

The candidate stops to chat up John Tuffin, a white factory worker. The conversation is friendly, although Tuffin tells me later that he’ll probably vote Conservative.

But so what? Here Galloway’s targets are the roughly 8,000 Bangladeshis who live in this part of the Isle of Dogs.

As the candidate, loudspeaker in hand, harangues from the courtyards of public housing complexes, hijab-clad women peer out from their doorways smiling.

“George Galloway,” he booms. “A big voice for the east end. A voice that cannot be ignored.”

To call Galloway a maverick does him little justice. An MP for 23 years — mostly with Labour — he has a history of irritating the brass.

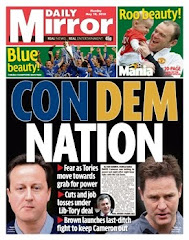

In 2003, Labour finally turfed him for his vitriolic opposition to the American-led invasion of Iraq.

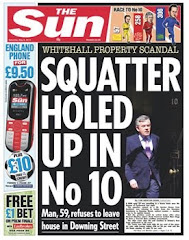

He is also a target for much of Britain’s fiercely partisan press. Seven years ago, one newspaper accused him of profiting personally from Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein’s regime (Galloway sued and won).

British authorities have three times looked into a whether a charity that he funds knowingly supports terrorism — and three times concluded that it does not.

And then, of course, there is Canada — which last year went so far as to bar Galloway from the country.

The ostensible reason was his much publicized effort to bring humanitarian aid into Gaza. Ottawa said this supported the Palestinian territory’s Hamas government, which Canada views as terrorist.

Galloway says he is still nonplussed by that. “I really don’t know whether to laugh or cry,” he says. “It was positively surreal . . .

“I’m not a supporter of Hamas . . . but I don’t complain about them. They are an elected government, the only democratically-elected government in the Arab world.”

He’s following with interest a federal court case launched by his Canadian supporters challenging the Conservative government ban.

Indeed, if there is a consistent thread to Galloway’s political career, it is his unwavering support for the Palestinians.

His epiphany, he says, came when he was a 21-year-old Labour Party worker. A Palestinian student walked into the party offices in Dundee and for two hours talked to Galloway about the plight of his people.

“By the end of those two hours, I was a paid-up member of the Palestinian resistance,” Galloway recalls, chuckling.

In 1977, he went to Lebanon for two weeks — and ended up staying 11 months. McKay, who met him there while covering the Lebanese civil war for the Sunday Times, describes the Galloway of that era as a “revolutionary tourist.” But Galloway remembers it as a far more serious period.

“I was kind of adopted by (then Palestinian leader Yasser) Arafat,” he says. “I would breakfast with him almost every day.”

But that is the serious side of Galloway. There is another.

In 2006, he agreed to appear on a British reality television show in a leotard lapping up imaginary cream from the cupped hands of a starlet.

His aim, he says, was to raise money for aid to Gaza (he did bring in the equivalent of about $750,000).

But the pussycat episode also left him open to withering media ridicule. Asked about it now, he only shakes his head. “If you don’t mind, I’m trying not to remember that,” he sighs.

Yet, even in this campaign, he can’t resist breaking the rules — the key one of which is to never insult voters. When one passer-by makes an impolite gesture at the campaign bus, Galloway growls through his megaphone: “There’s no BNP candidate standing here (running in this riding). You’re lost. You’re off your nutter.”

He says he’s sure he’ll win this race. But he also says that if he loses, he may just run next fall to be mayor of the local borough.

In fact, he says, even if he wins a seat in Parliament again, he may run for mayor anyway and do both jobs. “I’d promise to take just one salary. It’d be cheap.”

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

![Kay Jordan marched in Hanbury Street, Princelet street on 17 January 2006 [pictured below]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjmFpkcZgAW1eZKWId6O-xApvo7_zu4rL0QLz_ByB_FHaKbyUkAFfaPT1RdxXqjX-YVvveRu2zdPyr0pXqiFK-0SAjQd5vyTwGgGDnyU600Gk-gu-MueRhRIg_UhFT66fo8gzCl2tM4BX-8/s760/KHOODEELAAR%2521+No+to+Crossrail+Hole%252C+Demo+in+Hanbury%252C+Spelman%252C+Princelet+Streets+and+Brick+Lane+London+E1+17+January+2006.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment