1030 GMT

London

Tuesday

05 January 2010

By © Muhammad Haque

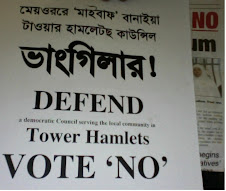

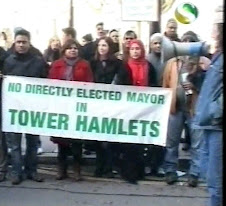

Growing trend in the community against the dangers of having an elected mayor in Tower Hamlets. But there is yet no campaign to reflect the trend!

Why there is no campaign yet, became clear at a meeting held yesterday in the Greatorex Street, off Hanbury Street off Brick Lane.

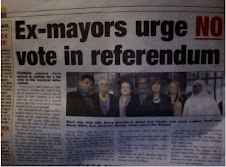

Although held as a ‘News Conference’, the event was manned by a number of current members of the Tower Hamlets Council. And it featured a few former councillors.

There were two documents distributed at the event. But they did not read anything like the contents of a campaign against having an elected mayor. They were like the product of a stale committee made up of clerks yielding words under the force of orders from their bosses. Somewhere in the deep depth of a bureaucracy unseen by and definitely unaccountable to the people.

Yet the words put on the wall behind the table used as the de facto platform declared ‘No” to an elected mayor in Tower Hamlets.

Most of the speeches, made by persons called with elaborate praise by the chair of the do, the ex-councillor Ala Uddin, were claimed to be arguments against having an elected mayor but lacked concrete and more worryingly, up-to-date substance on which to base a sustained campaign against the borough being lumbered with an elected mayor.

The ‘platform’ was making contradictory statements. Some were plainly inaccurate.

Here are two for instance:

One: We are NOT saying having an elected mayor is wrong.

Two: Good things can happened UNDER a mayor, as we have seen under Boris Johnson and Ken Livingstone.

If that event was any guide, those who may be claiming to be against an elected mayor in Tower Hamlets have a lot of work to do.

If they fail to do that then they will – wittingly or unwittingly – contribute to the eventuality that they said they were trying to prevent.

Tower Hamlets may end up with a mayor elected to office by default!

The challenge for all who genuinely recognise the dangers of an elected mayor is to make sure that there is credible and sustainable difference between what they represent politically to and in the community and those who are now going about calling for an elected mayor in the borough.

[To be continued]

Tuesday, 5 January 2010

SOCIALIST RESISTANCE Says No to elected Mayor

http://socialistresistance.org/?p=786

The trouble with elected mayors

The campaign by Tower Hamlets Respect for a referendum on having an elected mayor in the borough has refocused attention on the issue of democracy in local government. However, elected executive mayors are generally seen on the left as anti-democratic and tending towards over-concentration of power in the hands one person and a few senior officers. Indeed Respect activists have in the past campaigned to stop the spread of elected mayors for this very reason.

Who wants elected mayors?

The idea of elected executive mayors has its roots in the Blairite vision of local government, and was essentially imported from the US model of the “strong city Mayor”. It was turned into reality by the Local Government Act 2000. It represented a turn away from the traditional form of local governance whereby a ruling administration would be formed by the party (or coalition) which won a majority of council seats, to a system where all executive power is wielded by one directly elected individual, effectively sidelining the councillors (in a mayoral system the councillors have a token and largely meaningless role of “scrutiny” of decisions already taken elsewhere). This fitted in with the New Labour vision of a largely privatised local government.

And those sections of big business which contract for local government services have made no secret of their support for the mayoral system. One of the biggest contractors for local government services, Capita, stated in evidence to a House of Lords committee that they like the idea of –

“a strong leader who can personally commit the council making it easier for firms like theirs to develop partnerships”

The sub-text of this is of course that dealing with a single politician who can act without reference to anyone else makes it much easier for firms like Capita to snap up local government services. Rhetoric such as “being able to get things done” and “strong charismatic leaders” is often bandied about when the idea of an elected mayor is being hyped up in a locality. (One imagines that “strong charismatic leader” is not necessarily much of a selling point for anyone who knows anything about the last two thirds of the 20th century!)

Capita is one of a number of companies who signed up as “corporate partners” to the New Local Government Network, a Blairite thinktank which campaigns for “modernised local government”, elected mayors being a major component of this “modernisation”. The supporting companies are a veritable Who’s Who of public sector contractors, and the Confederation of British Industry itself is signed up. The links can be further seen in the person of New Local Government Network (NLGN leading) light Steve Bassam, former Brighton and Hove council leader, Labour peer, and sometime consultant to a number of these companies.

The NLGN donated substantially to one of the earliest campaigns for an elected mayor, in Brighton and Hove in 2001. This campaign was backed (and financed) almost exclusively by the business community, which in itself provides an object lesson about in whose interests the mayoral system operates. The only other backers were Bassam and a small number of New Labour politicians. The Labour group on the council was split on the issue and the idea commanded little or no support among Labour Party members, and was opposed by every other major political party in the city. A broad campaign involving political parties (including the Socialist Alliance), community groups and unions, with only a fraction of the budget of the pro-Mayor lobby, was able to defeat the proposal.

In some towns and cities, however, elected mayors did take off. London has an elected mayor, as do some London boroughs. We have also seen elected mayors in other places, such as Doncaster, Stoke and Hartlepool. Stoke Council has voted to scrap its elected Mayor, although as we will see, it is a lot harder to scrap a mayoral system than bring it in.

Ironically, Respect in Tower Hamlets is picking up this idea when it actually seems to be falling out of favour. There are currently just 12 elected mayors across the country, and despite the efforts of the NLGN, no apparent desire in most places to add to that number.

Where local referenda have voted in favour of an elected mayor, turnouts have often been low and margins narrow. For example, in Lewisham, the vote was 51% in favour of a mayor and 49% against, on a turnout of just 18%. This meant that only around 9% of Lewisham voters actually voted for a mayor. The Labour candidate, Steve Bullock, won the subsequent mayoral election even though Labour failed to secure an overall majority in the elections to the council – a clear demonstration of how elected mayors can wield power out of proportion to the overall popularity of their own party and to the complete exclusion of others.

In Brighton and Hove, the turnout in the No vote was a comparatively healthy 32%, suggesting that where there is a campaign on the ground alerting people to the dangers, they will turn out to vote it down.

The experience of elected mayors

The experience of mayors on the ground suggests that there is a clear democratic deficit. In Doncaster the previous incumbent, Martin Winter, was able to carry on in the post despite losing a vote of no-confidence from the council. Such a vote may put moral pressure on a mayor but there is no constitutional device to actually get rid of a mayor between elections. A campaign group in Lewisham found that there is no way to bring about a referendum on the scrapping of an elected mayor; only on having one.

There is also the evidence from London of how Johnson is using his position as mayor to drive through fare increases and make other concessions to the motoring lobby.

Do elected Mayors actually improve the performance of councils? Abjol Miah, Respect Group Leader on Tower Hamlets Council, claims they do, citing the example of Hackney. But in Doncaster, children’s services were officially branded “inadequate” under Winter’s rule. The evidence is, at best, inconclusive and contradictory. My own view is that many other factors affect “performance” – not least levels of investment and political priorities.

Another feature of the mayoral system is a tendency for candidates not from the traditional parties to be successful. This is no bad thing in itself, but often people will cast one vote for their chosen party for election to the council and a different one for mayoral candidate in the belief that they are “balancing” one against the other. In reality the ability of councillors to hold mayors accountable is extremely limited. Thus we have ended up with an English Democrat being elected to succeed Winter in Doncaster, “Robocop” Ray Mallon in Middlesborough, and the football club mascot in Hartlepool.

What is driving the Respect campaign in Tower Hamlets?

Firstly, it is true that the only allowed alternative to a mayoral system is a leader and cabinet system of governance. This is where the council leader rules with a cabinet group of councillors from the ruling party or coalition. It contains the same pitfalls as the mayoral system (centralisation of power, lack of accountability), but the mayoral system is no improvement. Yet the Tower Hamlets Respect campaign seeks to portray an elected mayor as somehow preferable.

Secondly, Respect activists in Tower Hamlets perhaps see their campaign as a blow against the political establishment, given that all of the other parties in the borough oppose elected mayors but this is simply because the leader and cabinet system suits them well enough. It does not in itself make an elected mayor a good thing.

This campaign also says something about how Respect has failed to develop a consistent approach to policymaking, which is what leads to these sorts of ad hoc decisions. It has also left Respect in the position appearing face two ways on this issue, given that Respect activists in other places have campaigned against this very proposal.

Respect’s priorities in local government should be around fighting for decent resources for councils alongside community groups and trade unions, and against the privatising agenda of the main parties. It should not be wasted on campaigns which seek to choose one system of undemocratic governance over another.

There Is 1 Response So Far. »

Comment by George on 3 January 2010:

It seems clear that the author does not understand the political dynamic in Tower Hamlets and is attempting to impose a ‘one size fits all’ assessment of the mayoral experiment on this specific situation. She or he also write as if Tower Hamlets Respect have not made their position on motivations for campaigning for a mayoral referendum absolutely clear (for example see http://towerhamletsrespect.wordpress.com/2009/11/11/why-we-need-an-elected-mayor/ and http://towerhamletsrespect.wordpress.com/2009/12/04/labour-know-they-are-losing-the-argument-on-an-elected-mayor/).

To summarise: no form of local democracy possible to acquire would be properly democratic. Two forms are currently on the table in Tower Hamlets. One of these maintains the power of unelected Labour bureaucrats over the machinery of the council. The other smashes this corrupt hold of unelected officials over ordinary people and contains the potential for a more genuinely representative leadership. Winning 50%+1 of the electorate is no minor thing.

I hope Socialist Resistance can recognise that in this concrete situation, to be neutral on such a matter, allowing Labour to continue to have their undemocratic way, is not an option.

Post a Response

Name (required)

Mail (will not be published) (required)

Website

The trouble with elected mayors

The campaign by Tower Hamlets Respect for a referendum on having an elected mayor in the borough has refocused attention on the issue of democracy in local government. However, elected executive mayors are generally seen on the left as anti-democratic and tending towards over-concentration of power in the hands one person and a few senior officers. Indeed Respect activists have in the past campaigned to stop the spread of elected mayors for this very reason.

Who wants elected mayors?

The idea of elected executive mayors has its roots in the Blairite vision of local government, and was essentially imported from the US model of the “strong city Mayor”. It was turned into reality by the Local Government Act 2000. It represented a turn away from the traditional form of local governance whereby a ruling administration would be formed by the party (or coalition) which won a majority of council seats, to a system where all executive power is wielded by one directly elected individual, effectively sidelining the councillors (in a mayoral system the councillors have a token and largely meaningless role of “scrutiny” of decisions already taken elsewhere). This fitted in with the New Labour vision of a largely privatised local government.

And those sections of big business which contract for local government services have made no secret of their support for the mayoral system. One of the biggest contractors for local government services, Capita, stated in evidence to a House of Lords committee that they like the idea of –

“a strong leader who can personally commit the council making it easier for firms like theirs to develop partnerships”

The sub-text of this is of course that dealing with a single politician who can act without reference to anyone else makes it much easier for firms like Capita to snap up local government services. Rhetoric such as “being able to get things done” and “strong charismatic leaders” is often bandied about when the idea of an elected mayor is being hyped up in a locality. (One imagines that “strong charismatic leader” is not necessarily much of a selling point for anyone who knows anything about the last two thirds of the 20th century!)

Capita is one of a number of companies who signed up as “corporate partners” to the New Local Government Network, a Blairite thinktank which campaigns for “modernised local government”, elected mayors being a major component of this “modernisation”. The supporting companies are a veritable Who’s Who of public sector contractors, and the Confederation of British Industry itself is signed up. The links can be further seen in the person of New Local Government Network (NLGN leading) light Steve Bassam, former Brighton and Hove council leader, Labour peer, and sometime consultant to a number of these companies.

The NLGN donated substantially to one of the earliest campaigns for an elected mayor, in Brighton and Hove in 2001. This campaign was backed (and financed) almost exclusively by the business community, which in itself provides an object lesson about in whose interests the mayoral system operates. The only other backers were Bassam and a small number of New Labour politicians. The Labour group on the council was split on the issue and the idea commanded little or no support among Labour Party members, and was opposed by every other major political party in the city. A broad campaign involving political parties (including the Socialist Alliance), community groups and unions, with only a fraction of the budget of the pro-Mayor lobby, was able to defeat the proposal.

In some towns and cities, however, elected mayors did take off. London has an elected mayor, as do some London boroughs. We have also seen elected mayors in other places, such as Doncaster, Stoke and Hartlepool. Stoke Council has voted to scrap its elected Mayor, although as we will see, it is a lot harder to scrap a mayoral system than bring it in.

Ironically, Respect in Tower Hamlets is picking up this idea when it actually seems to be falling out of favour. There are currently just 12 elected mayors across the country, and despite the efforts of the NLGN, no apparent desire in most places to add to that number.

Where local referenda have voted in favour of an elected mayor, turnouts have often been low and margins narrow. For example, in Lewisham, the vote was 51% in favour of a mayor and 49% against, on a turnout of just 18%. This meant that only around 9% of Lewisham voters actually voted for a mayor. The Labour candidate, Steve Bullock, won the subsequent mayoral election even though Labour failed to secure an overall majority in the elections to the council – a clear demonstration of how elected mayors can wield power out of proportion to the overall popularity of their own party and to the complete exclusion of others.

In Brighton and Hove, the turnout in the No vote was a comparatively healthy 32%, suggesting that where there is a campaign on the ground alerting people to the dangers, they will turn out to vote it down.

The experience of elected mayors

The experience of mayors on the ground suggests that there is a clear democratic deficit. In Doncaster the previous incumbent, Martin Winter, was able to carry on in the post despite losing a vote of no-confidence from the council. Such a vote may put moral pressure on a mayor but there is no constitutional device to actually get rid of a mayor between elections. A campaign group in Lewisham found that there is no way to bring about a referendum on the scrapping of an elected mayor; only on having one.

There is also the evidence from London of how Johnson is using his position as mayor to drive through fare increases and make other concessions to the motoring lobby.

Do elected Mayors actually improve the performance of councils? Abjol Miah, Respect Group Leader on Tower Hamlets Council, claims they do, citing the example of Hackney. But in Doncaster, children’s services were officially branded “inadequate” under Winter’s rule. The evidence is, at best, inconclusive and contradictory. My own view is that many other factors affect “performance” – not least levels of investment and political priorities.

Another feature of the mayoral system is a tendency for candidates not from the traditional parties to be successful. This is no bad thing in itself, but often people will cast one vote for their chosen party for election to the council and a different one for mayoral candidate in the belief that they are “balancing” one against the other. In reality the ability of councillors to hold mayors accountable is extremely limited. Thus we have ended up with an English Democrat being elected to succeed Winter in Doncaster, “Robocop” Ray Mallon in Middlesborough, and the football club mascot in Hartlepool.

What is driving the Respect campaign in Tower Hamlets?

Firstly, it is true that the only allowed alternative to a mayoral system is a leader and cabinet system of governance. This is where the council leader rules with a cabinet group of councillors from the ruling party or coalition. It contains the same pitfalls as the mayoral system (centralisation of power, lack of accountability), but the mayoral system is no improvement. Yet the Tower Hamlets Respect campaign seeks to portray an elected mayor as somehow preferable.

Secondly, Respect activists in Tower Hamlets perhaps see their campaign as a blow against the political establishment, given that all of the other parties in the borough oppose elected mayors but this is simply because the leader and cabinet system suits them well enough. It does not in itself make an elected mayor a good thing.

This campaign also says something about how Respect has failed to develop a consistent approach to policymaking, which is what leads to these sorts of ad hoc decisions. It has also left Respect in the position appearing face two ways on this issue, given that Respect activists in other places have campaigned against this very proposal.

Respect’s priorities in local government should be around fighting for decent resources for councils alongside community groups and trade unions, and against the privatising agenda of the main parties. It should not be wasted on campaigns which seek to choose one system of undemocratic governance over another.

There Is 1 Response So Far. »

Comment by George on 3 January 2010:

It seems clear that the author does not understand the political dynamic in Tower Hamlets and is attempting to impose a ‘one size fits all’ assessment of the mayoral experiment on this specific situation. She or he also write as if Tower Hamlets Respect have not made their position on motivations for campaigning for a mayoral referendum absolutely clear (for example see http://towerhamletsrespect.wordpress.com/2009/11/11/why-we-need-an-elected-mayor/ and http://towerhamletsrespect.wordpress.com/2009/12/04/labour-know-they-are-losing-the-argument-on-an-elected-mayor/).

To summarise: no form of local democracy possible to acquire would be properly democratic. Two forms are currently on the table in Tower Hamlets. One of these maintains the power of unelected Labour bureaucrats over the machinery of the council. The other smashes this corrupt hold of unelected officials over ordinary people and contains the potential for a more genuinely representative leadership. Winning 50%+1 of the electorate is no minor thing.

I hope Socialist Resistance can recognise that in this concrete situation, to be neutral on such a matter, allowing Labour to continue to have their undemocratic way, is not an option.

Post a Response

Name (required)

Mail (will not be published) (required)

Website

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

![Kay Jordan marched in Hanbury Street, Princelet street on 17 January 2006 [pictured below]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjmFpkcZgAW1eZKWId6O-xApvo7_zu4rL0QLz_ByB_FHaKbyUkAFfaPT1RdxXqjX-YVvveRu2zdPyr0pXqiFK-0SAjQd5vyTwGgGDnyU600Gk-gu-MueRhRIg_UhFT66fo8gzCl2tM4BX-8/s760/KHOODEELAAR%2521+No+to+Crossrail+Hole%252C+Demo+in+Hanbury%252C+Spelman%252C+Princelet+Streets+and+Brick+Lane+London+E1+17+January+2006.jpeg)